Political opportunists, racially charged ideologies, and colonial anthropologists have long appropriated and distorted the term “Aryan.” However, there is a deeper, much older meaning hidden behind the noise. In ancient Indo-Iranian languages, the word Arya simply meant “noble” or “noble men.” It referenced civilization, values, and character rather than race.

In the early second millennium BCE, the Aryans migrated from the Central Asian steppes and became a branch of the Indo-European peoples. They divided into two main groups as they traveled: the Iranian Aryans, who settled throughout Central Asia and the Iranian plateau, and the Indo-Aryans, who moved into the Indian subcontinent. Both groups brought with them spiritual beliefs, sacred languages (Avestan and Vedic Sanskrit), and a common identity based on the term Arya.

Genetic studies confirm what history and language already suggest: the Pamiri groups are among the most genetically preserved descendants of the ancient Aryans, with little to no admixture from later migratory populations. Among them, the Rushani (Roshanis) show the highest genetic continuity, followed closely by the Shughni and Wakhi. A 2012 study on Central Asian genetics revealed that Pamiries carry over 85–90% ancient Eastern Iranian (Aryan) genetic ancestry, with admixture from Turkic or Mongol sources being less than 10%—a stark contrast to surrounding populations. This genetic continuity, paired with their linguistic and cultural preservation, makes the Pamiries a living reservoir of Aryan heritage.

Pamiri groups are among the most genetically preserved descendants of the ancient Aryans.

Khorasan: The Land of Rising Sun

To understand the deeper historical and spiritual relevance of the Pamirs, one must revisit Khorasan, an ancient and often misunderstood term. During the Sasanian Empire, Khorasan referred not to a strict political region but to a civilizational and cosmological idea: “the land where the sun rises” (Khwar – sun; Asan – rising). This symbolic geography extended into present-day northeastern Iran, northern Afghanistan, southern Tajikistan, and northern Pakistan—precisely the range within which the Pamiri communities’ dwell.

If Khorasan was the spiritual sunrise of Iranian civilization, then the Pamirs were its gleaming summit. The word Pamir itself, as understood by locals, translates to “the foot of affection,” and is often poetically described as a place “where the sun gently touches the earth.” This metaphor goes beyond mere topography; it reflects an elevated cosmology, one deeply entwined with light, purity, and divine knowledge—central themes in Zoroastrianism, the ancient faith said to have originated in these very lands.

Zoroaster: Prophet of the Pamirs?

The legendary founder of Zoroastrianism, Zoroaster (Zarathustra), has long been associated with Eastern Iran. Yet numerous scholars, linguists, and historians are now placing his origins much farther east—in the mountainous Badakhshan region, particularly the Wakhan Corridor, which forms the spiritual and geographic heart of the Pamirs.

In a 1998 article published in Iranica Antiqua, Belgian Iranologist Prof. Jean Kellens noted that the earliest hymns of the Gathas (Zoroaster’s own words) contain descriptions of a highland region with flowing waters and brilliant light, a place untouched by urban corruption—a landscape astonishingly similar to the Pamirs, not the arid plateaus of modern-day Iran.

Moreover, the Avesta, Zoroastrianism’s sacred text, describes Airyanem Vaejah—the first land created by Ahura Mazda—as a mountainous, lush, and sacred place. Although its precise location has been debated, contemporary scholarship increasingly places it in the Pamir-Alay range, a view supported by scholars such as Michael Witzel (Harvard) and Ilya Gershevitch. Linguistically too, the Eastern Iranian languages spoken by Pamiries, such as Wakhi and Shughni, preserve grammatical and lexical features closer to Avestan than Persian or Pashto.

It is no longer merely poetic to propose that Zoroaster may have been a Pamiri himself. Rather, it is a thesis gaining traction across linguistic, historical, and mythological domains.

The Last Aryans

Today, the last communities of these original Aryans—culturally, linguistically, and genetically preserved—can be found not in textbooks but in the towering valleys of the Pamir Mountains. Five distinct ethnolinguistic groups call this high-altitude sanctuary, straddling Tajikistan, Afghanistan, China, and Pakistan, their home.

• Shughni:

The largest Pamiri group, inhabiting both Badakhshan Province in Afghanistan and Gorno-Badakhshan in Tajikistan. Their language, Shughni, acts as a kind of lingua franca among Pamiries.

Estimated population: ~130,000

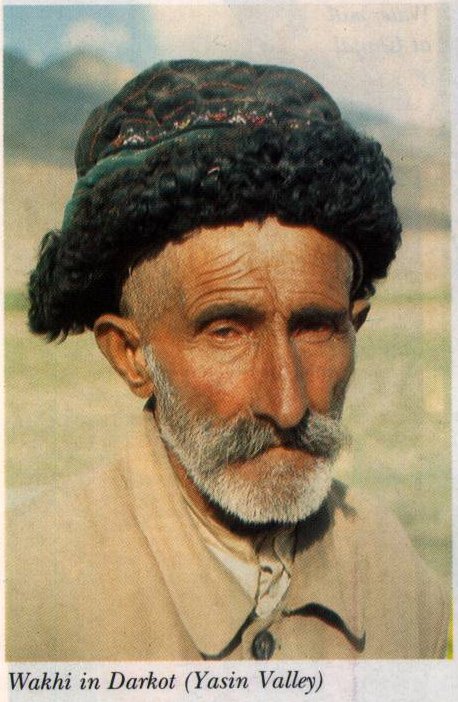

• Wakhi:

Geographically the most dispersed, the Wakhis are found in Tashkurgan in China, Wakhan in Afghanistan, Gojal in Pakistan (Upper Hunza), and Gorno-Badakhshan in Tajikistan. Their way of life is greatly impacted by transhumance and high-altitude pastoralism, and their language still has many archaic Iranian characteristics.

Estimated population: ~80,000

• Rushani:

Inhabiting Tajikistan’s Rushan District and nearby Afghan regions, the Rushani retain unique phonetic structures that distinguish them even within the Pamiri cluster.

Estimated population: ~30,000–40,000

• Ishkashimi:

Native to the Ishkashim District on the Tajik-Afghan border, their language is critically endangered but retains ancient Iranian features.

Estimated population: ~6,000–8,000

• Yazgulyami:

The most remote group, found in Tajikistan’s Yazgulem Valley. Their language is perhaps the most conservative of all Pamiri tongues.

Estimated population: <4,000

Heritage Under Siege

Despite their profound historical significance, Pamiri communities are under existential threat. In Tajikistan, they face political marginalization and periodic crackdowns. In China, the Wakhi Pamiries endure religious restrictions. And in Afghanistan, their faith and identity place them at risk under extremist rule.

Ironically, the only sanctuary for Pamiri culture today is found in the south, in Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan region, where the Wakhi Ismaili community lives without state persecution. While development challenges remain, Pakistan offers an open space for the free practice of their spiritual life, bolstered by the Aga Khan Development Network’s presence.

The Aryan legacy is not a relic of racial myth, but a living, breathing tradition thriving in the silence of the Pamir highlands. It is in the stone homes, the sacred poetry, the glacial waters, and the whispering dialects of the Pamiries that one finds the clearest reflection of an ancient ethos—perhaps even the footsteps of Zoroaster himself. Their survival is not merely a cultural concern; it is a call to recognize and preserve one of humanity’s last living links to the dawn of civilization.